12/7/2021

“The world is slowly transforming into the vaccine haves and the vaccine have nots… This inequity is not just a moral failure but a scientific failure.”

Professor Madhukar Pai

The year 2020 marked the beginning of a new decade. While many people were left perplexed as COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March, it ended with lots of hope and optimism as vaccines were being rolled out.

As of June 21, 2021, only 21.8% of the world’s population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, compared to countries like Canada and the U.S., with more than 50% of the population having received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine (Our World in Data, 2021). This disparity becomes even more clear as many countries in the African continent have not yet vaccinated 1% of their population.

An infection that the whole world encountered, had and continues to have a different morbidity and mortality depending on the country in which people reside, the social determinants of health, and the health system’s response to the pandemic.

At first glance, the vaccine coverage may appear as a separate issue – unrelated to the observed health disparities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, this is not the case and there are some fundamental lessons to be learned from the past year.

If these lessons are not considered in the current pandemic response, it could lead to more severe disparities in vaccine coverage and further strain health systems and its six building blocks: i) service delivery; ii) health workforce; iii) health information systems; iv) access to essential medicines; v) financing; and vi) leadership/governance (World Health Organization, 2017).

The following are three main lessons that we can learn from how the COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded:

Lesson 1 – Implement evidence-based practice to address vaccine hesitancy

Lesson 2 – Invest in health to attain vaccine affordability

Lesson 3 – Increase solidarity and support vaccine equity

One of the giant pitfalls, especially with the evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the lack of adherence to evidence-based medical and public health practice.

In a rush to respond to the pandemic and the time pressures healthcare providers experience, patients may not always receive the best care and treatment options, sometimes resulting in adverse health outcomes.

These challenges applying evidence-based practices was a reality across the world, including countries that are known to have stronger health systems.

Non-scientific recommendations and mixed messages by country leaders contributed to the defiance of mask wearing and physical distancing, misinformation, and many other examples that interfered with the COVID-19 response (Carley et al., 2020; Hotez, 2021).

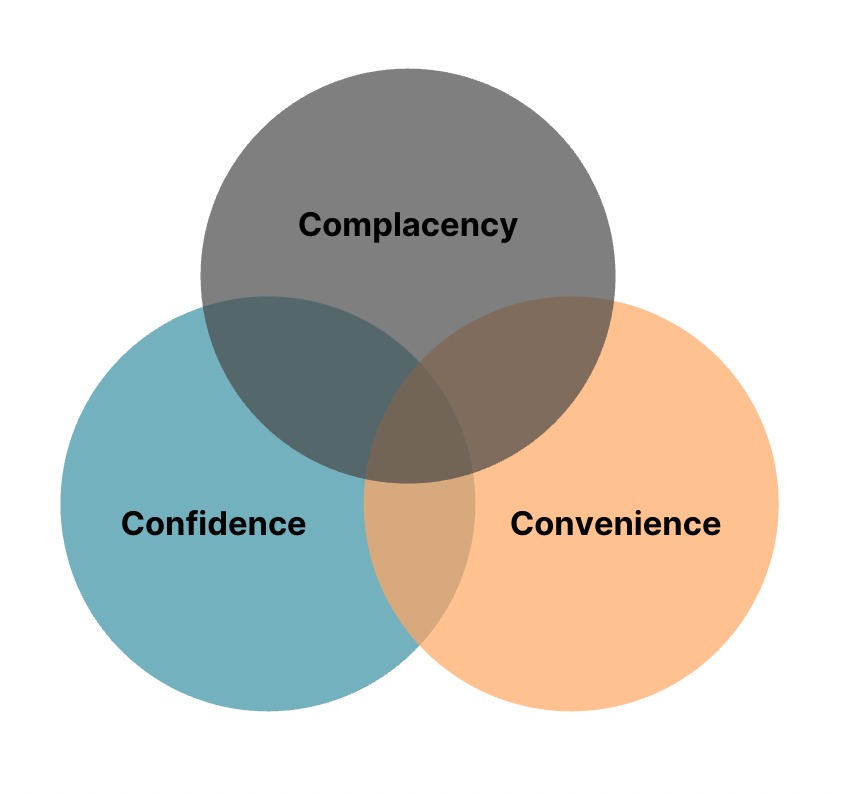

According to the 3Cs model (Figure 1), vaccine hesitancy is influenced by confidence, complacency, and convenience and each of these can be addressed using evidence-based strategies (World Health Organization, 2007).

In an article by Rutten LJF et al (2021), the authors encourage different levels of interventions that can be taken to offer evidence-based solutions and overcome vaccine hesitancy.

These interventions include individual interventions (e.g., patient and clinician education), interpersonal interventions (e.g., recommendations, presumptive-announcement style language), and organizational interventions (e.g., orders, audit and feedback, reminders and recalls, point of care prompts) (Finney Rutten et al., 2021).

Health systems, with the support of their respective governments, should make a more concerted effort to put these evidence-based strategies into practice and improve the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines.

Since health systems were not adequately prepared for the pandemic, many countries created ‘extra budgetary funds’ (EBFs).

A note from the International Monetary Fund published in August 2020 describes the different emergency funds set up by countries as well as the associated pros and cons (Rahim et al., 2020).

While these funds can be programmed and disbursed quicker than the conventional budget process, they entail fiscal risks and corruption vulnerability.

Unlike the start of the COVID-19 pandemic that may have been mostly unexpected, governments had more time to plan and prepare for vaccination programs.

A major contributor for the rapid development of vaccines was the billions of dollars that governments and donors invested in the Research & Development (R&D) for vaccines.

This investment should not stop at R&D, it must continue beyond to fund costs associated with the distribution and administration of the vaccines.

The COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access (COVAX) initiative for sharing vaccines also requires substantial funding and is still 2.2 billion USD short of its funding needs for vaccination this year (World Health Organization, 2021).

The importance of investing in health has only been re-emphasized by this pandemic and it is time for governments and world leaders to act.

The initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic included border closures and national lockdowns. Many borders remain closed in 2021 for international travel.

The goal of these measures is to help reduce the spread of the infection, and not to leave us even more isolated and indifferent to the struggles of our neighbouring nations.

As some countries have now achieved promising vaccination rates, it is important to not turn a blind eye to how the pandemic is impacting the rest of the world.

While some health systems may celebrate the robust vaccine coverage for their populations, there are people in different parts of the world where access to healthcare and essential supplies, such as oxygen, are still a daily challenge.

As Dr. Tedros often says, “none of us will be safe until we are all safe”. This realization is vital for world leaders who must move “from nationalism to internationalism, from charity to solidarity, and from competition to cooperation” (Mayta, Shailaja, & Nyong’o, 2021).

Global citizens should be aware of the importance of vaccine equity and must continue to advocate for an equity-based strategy (Pai, 2021).

Hindsight is 2020 and we may not be able to travel back in time to invest adequately or express solidarity in our COVID-19 response. However, it is not too late for health systems to correct this course to achieve vaccine equity.

Though global decision-makers may have missed the mark on health equity during the first year of the pandemic, the mistakes can still be rectified through equitable and widespread access to COVID-19 vaccinations.

Our World in Data. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. Access here.

World Health Organization. (2007). Everybody’s business — Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO’s framework for action. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2007. Access here.

Carley S et al. (2020). Evidence-based medicine and COVID-19: what to believe and when to change. Emerg Med J;37:572–575. Access here.

Hotez PJ. (2021). America’s deadly flirtation with antiscience and the medical freedom movement. J Clin Invest.;131(7):e149072. Access here.

World Health Organization. (2011). WHO EURO Working Group on Vaccine Communications. Istanbul, Turkey. October 13–14. 2011

Finney Rutten LJ, Zhu X, Leppin AL, Ridgeway JL, Swift MD, Griffin JM, St Sauver JL, Virk A, Jacobson RM. (2021). Evidence-Based Strategies for Clinical Organizations to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clin Proc.Mar;96(3):699-707. Access here.

Rahim F et al. (2020). COVID-19 Funds in Response to the Pandemic. International Monetary Fund. Access here.

World Health Organization. (2021). Access to COVID-19 tools funding commitment tracker. Access here.

Mayta R, Shailaja KK, Nyong’o A. (17 June 2021). Vaccine nationalism is killing us. We need an internationalist approach. The Guardian. Access here.

Pai M. (15 April 2021). 10 reasons why everyone should advocate for Covid-19 vaccine equity. Nature Microbiology. Access here.